Hideo Yokoyama’s sixth novel, Six-Four, is his first to be published in English, appearing in early 2017 under the imprint of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, and weighing in at 566 pages. My knowledge of Japanese detective fiction is admittedly limited. Aside from having read all of Haruki Murakami’s books, the only other Japanese book I’d read before Yokoyama’s novel was Natsuo Kiruno’s Real World, another crime novel.

Hideo Yokoyama’s sixth novel, Six-Four, is his first to be published in English, appearing in early 2017 under the imprint of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, and weighing in at 566 pages. My knowledge of Japanese detective fiction is admittedly limited. Aside from having read all of Haruki Murakami’s books, the only other Japanese book I’d read before Yokoyama’s novel was Natsuo Kiruno’s Real World, another crime novel.Yoshinobu Mikami, a former homicide detective recently appointed as press director, finds himself fighting many battles. His teenage daughter has run away from home. His relationship with his wife, Minako, herself a former police officer, is crumbling under the stress of their daughter’s disappearance. Meanwhile, he is assigned from homicide to become the director of the press relations group, and feels veru much like a fish out of water.

Mikami is new in his role, still finding his feet when balancing police needs to keep certain details from the the public while still satisfying a hostile press corps who question that very need for secrecy. Almost from the outside he finds himself at odds with the press contingent that covers crime and the police, when he withholds the name of a person involved in a fatal car accident. The fact that this person is connected to a government official makes his position more delicate. To the press that news would become a leading story, no matter any extenuating circumstances. The small but loyal police press department consists of two young male assistants (one of whom likely envisions himself one day in the job of press director himself), and a young female officer busted moved over from the transportation division. Mikami places himself almost in a fatherly role with the young Mikumo, limiting her contact with the devious and salacious members of the press, who frequent karaoke bars with the police outside work in a two-way street in terms of information and disinformation efforts.

As if dealing with the press and disappearance of his daughter wasn’t enough, Mikami also finds himself fighting internal political battles inside the police department. The press division isn’t the greatest of tasks, and supervisors and other divisions appear to be plotting against Mikami in various internal battles, jockeying for future appointments within the precinct and greater Tokyo police force infrastructure. A former classmate seems to be behind many of the plots, at least as envisioned by Mikami. This person, Ishii, hovers in the background, runs unofficial investigations of past cases. One such past case, Six-Four, becomes yet again a present case, as a high-ranking inspector from Tokyo plans a visit to pay his respects to the dead girl’s father, Yoshio Amamiya, who has suffered in silence for many years, and lost his wife one year ago, compounding his pain.

To facilitate the meeting between Amamiya and the police contingent, Mikami is sent to pave the way, both in his role as press director and as a detective from criminal investigations who worked the case, which remains unsolved to this day and weighs heavy on Mikami. The initial meeting doesn’t go well, and Mikami emerges with the feeling that he has failed his role, a feeling compounded during a meeting with his superiors. In that meeting the seeds are sown in his mind about internal plots within the department, various groups working at odds with each other, and maybe at the root is the failure of the Six-Four case fourteen years ago.

Events accelerate when a copy-cat crime takes place, with another young girl kidnapped and the exact same process as in the previous crime repeats itself. Finding himself at the center of various threads, from a rebellious and antagonistic press to imperious commanders and police chiefs seemingly plotting against him, Mikami sees the new case as a way to atone for past wrongs, and dives into his own investigations.

Although some of the plot points seems byzantine and contrived, Yokoyama’s massive novel became impossible to put down once the various plots had settled into their individual paths. The language is sparse, economical. As a reader I felt almost one with the protagonist, felt his paranoia and anguish, and wondered how the various elements would come together. Not everything is tied neatly at the end, and some mysteries remain, but Six-Four is one of the best crime novels I’ve ever read. Admittedly it felt slow to start, and the dispute with the press somewhat contrived, but the characters come to life in the pages. I should also note that the book was made into a two-part movie. I’m not sure if this was for the big screen or television, as I watched it this summer on an intercontinental flight between the UK and US. The movie remained relatively faithful to the book, something probably difficult for a book of that length and complexity.

Although I have generally moved away from reading science fiction and fantasy, there are a few writers I never will abandon.

Although I have generally moved away from reading science fiction and fantasy, there are a few writers I never will abandon.

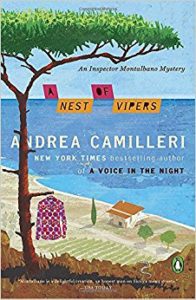

Andrea Camilleri’s latest Montalbano novel is disappointing on many levels. Not until you read the afterword do you learn that, although it was published in the US in August 2017, that Camilleri wrote A Nest of Vipers back in 2008. Camilleri notes that it was held back as the theme was too similar to his 2004 novel, The Paper Moon. The so-called similarity is not the most disappointing aspect, at least to me. Rather, with Montalbano aging (ever so slightly) with each novel, I had looked forward to reading more about the ramifications from the two previous novels, A Beam of Light and A Voice in the Night. With 20 plus novels sketching Montalbano’s life, each one takes us little further, and A Nest of Vipers fails in that regard.

Andrea Camilleri’s latest Montalbano novel is disappointing on many levels. Not until you read the afterword do you learn that, although it was published in the US in August 2017, that Camilleri wrote A Nest of Vipers back in 2008. Camilleri notes that it was held back as the theme was too similar to his 2004 novel, The Paper Moon. The so-called similarity is not the most disappointing aspect, at least to me. Rather, with Montalbano aging (ever so slightly) with each novel, I had looked forward to reading more about the ramifications from the two previous novels, A Beam of Light and A Voice in the Night. With 20 plus novels sketching Montalbano’s life, each one takes us little further, and A Nest of Vipers fails in that regard.