After the “approach trail,” which apparently not all thru-hikers take, I went another three or so miles to Stover Creek Shelter. My total distance hiked for the first day was ca. 12 miles. At Stover Creek, I set up my tent, then made my major mistake of the hike, one I would repeat one more time: I failed to eat dinner. Instead, I crawled into my tent around 6pm and just tried to sleep, despite sundown still two hours away. Even though I wasn’t tired, I felt that I needed the rest, and also I didn’t feel hungry enough to heat a freeze-dried meal. Nor did I think of a snack at this point.

One of the things I learned in my over 500 miles of hiking along various trails is that consistently I fail to properly fuel while hiking. I lose my appetite somewhere along the trail, and I struggle to eat solid foods, either power bars nor rehydrated food. I eat sparingly, and pay the price near the end of the day. This is far from ideal, as hiking multiple miles in one day meals that calories are burned, and the body needs to be replenished. I probably also do not drink enough water, although I made an effort on this trail. I carrier three liters of water, and refilled my water bottles often along the way, using both a filter and purifying tablets. The days were hot, and I made myself drink fairly often as I walked. Still, I probably didn’t drink enough.

First day, not so bad, I thought. I camped where I planned to camp. The next day, I planned to hike to Gooch Gap Shelter, another 12 or so miles from the Stover Creek Shelter. I woke up early, packed up my tent and gear, ate a breakfast bar, and set out on the trail around 8am. At first, I took it slow, enjoying the green tunnel and silence, until I was passed by another hiker. Then I re-evaluated my pace and went from a stroll to something faster. Another mistake. Hike your own pace is the key. However, from now on I measured myself against this hiker’s pace, as we would leapfrog each other time and time again in my days on the trail. This shadow of mine was a thru-hiker, around twenty years younger, and quite motivated. Along the trail I’d encounter at least five other thru-hikers, plus some section-hikers like myself. They each had amazing stories behind the reason for hiking the AT. Had I known about the AT in my early thirties, maybe my life would have been different.

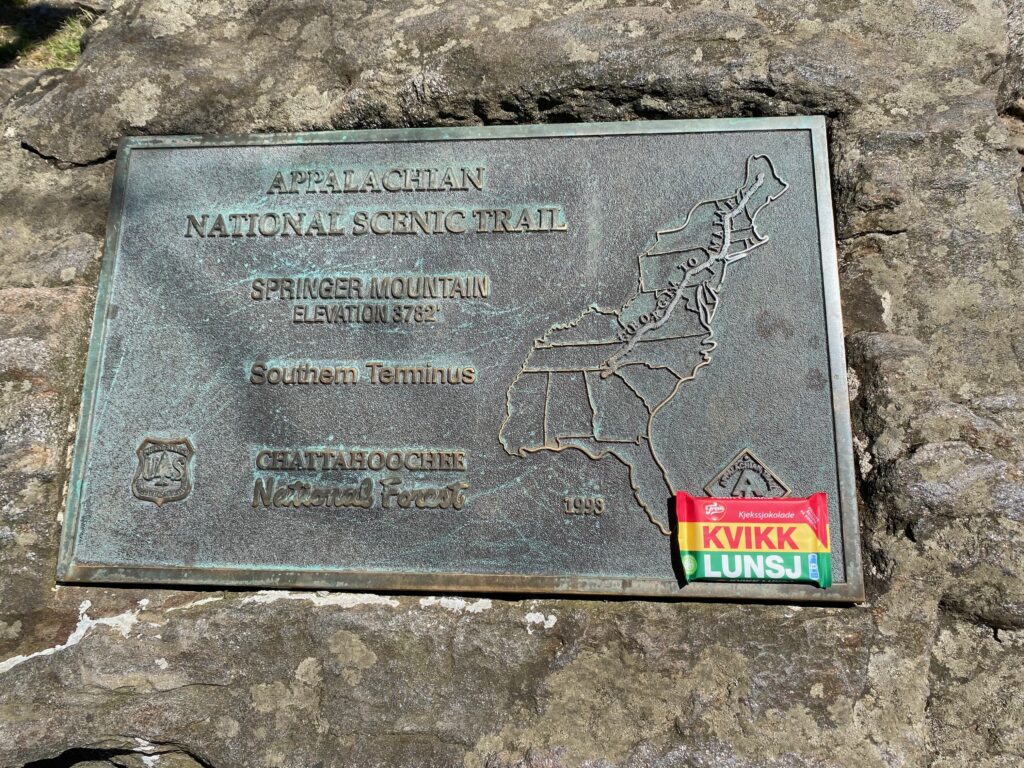

Nothing prepares you for the AT (or probably any long distance trail). Not watching multiple YouTube videos. Not reading blogs and hiker diaries. Not reading many books about thru-hikes and attempted thru-hikes (I’m looking at you, Bill Bryson). I’ve hiked in Big Bend, Bryce Canyon, northern New Mexico, in Nevada, plus various locations in Norway. Most of the trails in these location have moderate hills, or one big climb. Not the AT. The AT is an almost constant up and down trail, at least in northern Georgia, with each mountain interspersed with “gaps.” After while, when I saw a sign announcing a gap a few miles ahead I groaned, for I knew this meant a big downhill and then a big uphill, again and again.

After Three Forks there was a waterfall. I plowed onward and uphill, bypassing the Hawk Mountain Shelter and campsite, then Hightower Gap, Horse Gap. Somewhere along here I took a break by a creek, where the four women I’d met on Springer also were taking a break. They’d hiked from Springer to Hawk Mountain their first day, and were planning to hike as far as they could over the span of five days. We chatted for a while before I headed back on the trail. And then, Sassafras Mountain. This was a brutal climb.

After resting at the top of Sassafras, it was downhill to Cooper Gap, where I took a long break to eat and recuperate. Next, I crossed a creek, with a sign pointing to a campsite just north of the creek. My goal was Gooch Gap Shelter, so I kept walking. The last mile was tough, and I started asking out loud, “Gooch Gap, where are you?” I crossed another creek, where two older hikers were filling up on water, and then, finally, Gooch Gap Shelter.

I found a vacant tent pad, set up my tent, and worked on making dinner and filtering water. After another 12 mile day I was exhausted, but I forced myself to eat a freeze-dried meal that I heated up. I’m not sure what it is with these freeze-dried meal packets, but they tend to overstate the amount of water needed. They’re also designed for two portions. Instead of a nice meal, it was more like semi-soup, but I ate half before I gave up. The day had been hot, 85 degrees F. Where I’d pitched my tent the sun shone directly on it, and I had more than two hours until sunset. I tried to sleep, then took a break to visit the privy. I’m not sure if people just can’t handle public toilets, but it looked gross, and I had to close my eyes to do my business. Then, back to the tent and solitude. The thru-hiker I’d camped next to at Stover Creek was there, but he strongly hinted that he didn’t want a close neighbor, so I’d set up my two pads below his tent. Another thru-hiker camped between us, and they chatted a long time. I found my noise-canceling headphones and enjoyed a brief moment of silence. Finally the neighbors stopped talking, and I managed to fall asleep. At some point during the night, a third thru-hiker had pitched his tent next to the first one, so he ended up with a close neighbor anyway. As for the night, I woke up multiple times to snoring from the nearest neighbor. Good times.

To be continued….