Michael Shea’s Nifft the Lean is one of the best fantasy books ever written. Sadly, you won’t see it on many so-called “best of ” lists. It won the World Fantasy Award in 1983, though it was unfamiliar to me until a few years later. I encountered Shea via Jack Vance, whose works I first read in 1985. I can’t remember if I bought the DAW edition of Nifft in Norway, as I lived there between 1983 and 1988. I know I bought at least two or three Shea books in Norway, including the Jack Vance-inspired novel, A Quest for Simbilis. I likely also bought In Yana, the Touch of Undying, and The Color out of Time there, but the rest of them I probably found in the US after I moved there in 1988. A book published in 1982 likely then either lingered on a shelf in specialty book stores, or in the many used paperback book stores found in Austin in the 1980s and 1990s (most of those bookstores probably died off after 9/11, as they’ve now all vanished, only Half Price Books remaining, at least the last time I checked).

The first Arkham House book I bought was Shea’s Polyphemus, which at $16.95 when I found it at Austin Books in 1988 or 1989 seemed an extravagance far beyond my means. At once point I tried to find every short story published, thinking I’d try my hand at publishing a book: the complete collection of Michael Shea stories. Of course, nothing happened as I had no experience in that field. Besides, Centipede Press beat me to that task (almost; not all published Shea stories were included in The Autopsy and Other Tales, a massive edition published in 2008; only 500 copies were printed, and I own # 106.)

I wrote a few reviews of Shea books over the years, and I know at least one of those reviews received a comment to the magazine editor from the author himself. I never got to meet Shea, as I didn’t attend many conventions outside Central Texas. It was truly a sad day for me when I learned of Shea’s death in 2014. What surprises me to this day is that at least two of his novels remain unpublished, as well as the nearly finished fourth volume in the Nifft series. This is according to Shea’s Facebook site, from a mention by his wife, Linda Shea. Publishers: please consider bringing these books to the world!

In 1994, Wildside Press published a limited edition of Nifft the Lean, a rare book to find even in the 1990s. BAEN Books reprinted it in a paperback edition along with The Mines of Behemoth, but that was years ago.

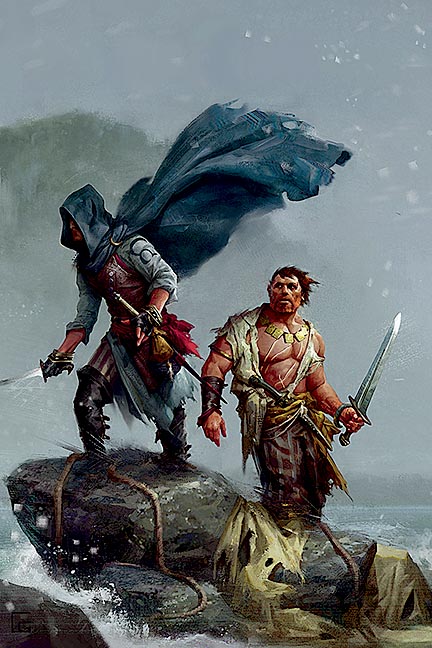

Then, in 2020, Centipede Press issued a new edition of Nifft the Lean. This edition has a foreword by Tim Powers (though an old one), as well as an afterword by Michael’s wife, Linda Shea. The book, as with all Centipede Press books, is a wonder to behold and hold. I’ve read the DAW edition from 1982 many times, each time holding it carefully as I turned the now-brittle and fading pages. Although the new book is a welcome edition (and addition) to my small library, it’s still sad that such a book only appears in limited numbers. Then again, maybe Shea’s an acquired taste. The prose is somewhat purple, the setting maybe to dark for some readers. Years ago a publisher called Pyr Books brought out SF and Fantasy books in trade paperback editions. I immediately knew which books were fantasy, as there always was a sword somewhere on the cover. Shea’s characters don’t always wield swords, yet there are other, more vivid (in my mind) elements of the fantastic within his stories, than in many “modern” fantasy tales.

The CP edition has the number “1” on the spine. I take it to mean there will be more hardcover editions to follow. I eagerly look forward to those; my wallet, not so much.