One thing leads to another. In one of the recent James R. Benn novels about army investigator Billy Boyle, the protagonist picks up a copy of Nevil Shute’s 1942 novel, Pied Piper. I have half a dozen Shute paperback in my library, but I didn’t recall having read this particular book. Naturally, I had to check whether or not this one of the books in my library, and found that indeed, I owned a copy.

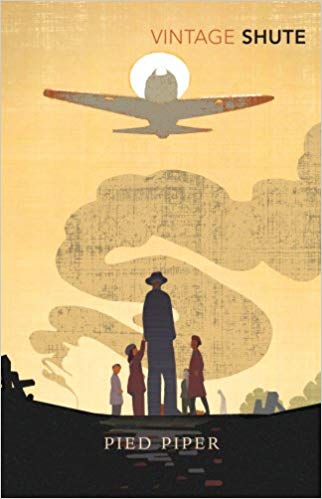

Who knows where I picked up the British edition, with a list price of £3.99, printed in 1992. I read the back cover, which barely hints at the story within. Told as a story within a story, Pied Piper takes place in France just before and after the German invasion of France and the British evacuation at Dunkirk. An older man, near seventy, tells a story to a younger man in a club in London, as bombs from the Germans rain down outside.

Howard, by some strange decision, traveled to France in the Spring of 1940, even as Germany and Britain were at war. Perhaps in those days, people though France was safe, while Switzerland likely would suffer the fate of Austria. Howard traveled to the Jura mountains for a fishing expedition, carrying with him a special set of poles, and wet flies. While at the hotel, he learns of the German invasion of Norway, and their advance through Holland and Belgium. He decides it’s best to head back to England. A couple, the man working for the League of Nations in Switzerland, ask him to take their young children to England, thinking the journey safer than returning to Zurich.

Howard agrees, and begins a long journey toward Dijon and Paris, eventually the coast and over to England. En route, plans change. The Germans storm into France, throwing rail service into chaos. The youngest child catches a fever; they are forced to rest along the way, picking up a 10-year-old girl whose father works in England. They switch from trains to bus. The road gets bombed by Germans, and they continue on foot, picking up another child, an orphan as a result of the bombs. In another city, an additional child joins their band. Howard gains a helper, a woman who knew his son. As Howard later learned, that woman almost became his daughter-in-law, had his son not died in an RAF bombing raid, being a pilot in the midst of the war.

Will Howard and his band of children make it to the coast, and if they get there, will they evade the Germans and reach England? As the blurb on my book cover says, “You have to read on and on.” Shute’s style is basic, but he spins a compelling tale. Some of the mores are rooted in an earlier age, but the sketches of the French and French countryside uniquely French (at least from an outsider’s perspective). It’s a tale born of tragedy—Howard’s son’s death—love, courage, kindness, and fear.