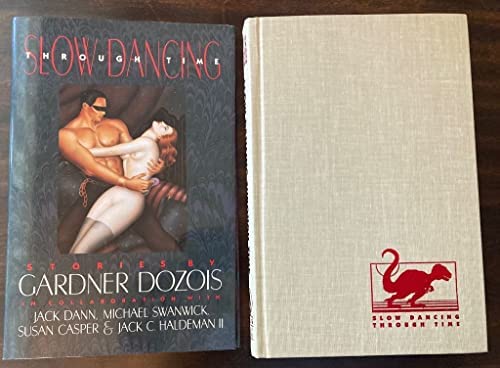

Recently I bought a collection of stories, a set of collaborations between Gardner Dozois and other writers, called Slow Dancing Through Time. When I bought it I didn’t realize that I’d bought the special limited edition, and that it came in a slipcase. Published by Ursus/Ziesing back in 1990, this book is one of 374 numbered and lettered copies signed by all contributors, including Dozois, Pat Cadigan, Michael Swanwick, Jack Dann, Jack C. Haldeman II, Susan Casper, Michael Bishop, Tim Kirk, Vern Dufford, and Dick Ivan Punchatz (the latter three the illustrators). A trade edition also appeared, though in an unknown number.

It’s a beautiful book, with a wonderful illustration inside the front and back covers by Tim Kirk. It’s a book I’ve seen previously somewhere, but without remembering where. Possibly at some SF convention. Reading it now, more than 30 years later, with several of the contributors no longer alive, is a strange feeling. A book like this doesn’t feel 30 odd years old, or maybe I don’t feel that the passage of time has stretched so long from 1990 to the present.

Collections and anthologies are an interesting breed of book. Writers of short stories usually sell their stories to magazines, and they sell enough, and reach a certain degree of fame, sometimes succeed in getting several of their stories published in a collection, or an anthology of like-minded tales. When it comes to books, the novel market dominates. Short story collections usually only appear in smaller print runs, unless you’re someone like Stephen King. They thrive within the embrace of small press publishers, as these publishers generally have print runs of a few thousand copies. The great part about collections is reading short works of fiction, but what I find just as much fun is reading the intros. These may be in the form of the general introduction, usually where the author bemoans the lack of markets for short stories, and the limited press run of their collection, how they begged and pleaded for their publisher to cobble together this great volume. Or, they could be smaller intros to each story (or in some cases, afterwords, where the writer patiently asks the reader to make sure that the reader actual read the story before the afterword—sometimes unsuccessfully, I might note in my case).

Some writers seem to put as much work into their introductions, as their stories. Harlan Ellison is like that. Others try to let the stories speak for themselves, such as Jack Vance, who only wrote a few brief intros to his collections. Part of my fascination with the non-story pieces is because these often are insights into the mind of the author, who tries to recreate the genesis or meaning of the story. This isn’t something you can do we you write a story, but once written many writers seem to want to look backward and try to explain, to themselves as much as to the reader, how that story came about and what it means to them.

Perhaps, at least in my case, the juxtaposition of the story and the accompanying pieces are a reminder of the work that goes into any fiction, even quite short ones. Good short stories must have an impact, a short sharp shock. A simple joke told by a comedian has been honed and re-written multiple times, to reach the payoff. A short story has been conceived, written, stripped down to its essentials. After that effort, getting an insight into what brought that story to life adds to it, makes the writer seem human and not like some god.

The intro, afterword, or whatever one calls that accompanying text, provides not only insight into the genesis of a story, but the time and place around that story. Sometimes the writer will go into detail how they sold it to a book or magazine. Many of these no magazines no longer exist, or seem like strange choices. Some stories have a winding life until they finally find a home, or end up forgotten and alone until restored among its siblings in a volume of the author’s work.

Collections without such intros are often sad, sterile affairs. Sure, you can read the stories, but by themselves they feel, well, empty. That, of course, is the personal choice of the author who’s likely not getting paid by the word for writing those non-fictional pieces. It does seem a shame, in the age of the internet, but even prior, that many of the short story markets and publications no longer exist. From the pulps to the slick, to specialty magazines and fanzines, many now lie lost and forgotten. Such is it, I suppose, with some older writers, whose books no longer are in print. The genre market is a tough one, even for living authors. Dead ones for the most part now also live in the past. Rediscovering this volume maybe keeps their memory alive a little longer.