Michael Shea (1946-2014) remains one of my top five fantasy writers, along with Jack Vance, Clark Ashton Smith, Fritz Leiber, and James P. Blaylock. I’d include Tim Powers there, and maybe shift Blaylock out of the mix in favor or a more traditional fantasy writer like Lord Dunsany or possibly Charles de Lint, but Powers, Blaylock, and de Lint stand slightly off to the side in terms of traditional fantasy. Powers is more science-fantasy, and de Lint’s urban fantasy doesn’t venture as much into the realm of the weird as the others listed. Blaylock lately has written a fair amount of Steampunk, but his other tales are infused with a subtle fantasy similar to Powers.

Michael Shea (1946-2014) remains one of my top five fantasy writers, along with Jack Vance, Clark Ashton Smith, Fritz Leiber, and James P. Blaylock. I’d include Tim Powers there, and maybe shift Blaylock out of the mix in favor or a more traditional fantasy writer like Lord Dunsany or possibly Charles de Lint, but Powers, Blaylock, and de Lint stand slightly off to the side in terms of traditional fantasy. Powers is more science-fantasy, and de Lint’s urban fantasy doesn’t venture as much into the realm of the weird as the others listed. Blaylock lately has written a fair amount of Steampunk, but his other tales are infused with a subtle fantasy similar to Powers.

Shea, however, with his novels and short stories, is firmly in the fantasy camp, with a dash or horror in some of his short stories. His death came all-too-soon, with several novels still in the pipeline and his genius far from fully recognized.

I first encountered Michael Shea’s writings in 1986 or 1987 when I bought his unofficial sequel to Jack Vance’s Eyes of the Underworld. Although A Quest for Simbilis first appeared in 1974 under the DAW imprint, my first copy was the Grafton paperback edition published in 1985, which I bought in Oslo or Bergen at a book store or bus station; it was a long time ago and I don’t remember the exact details . At some point later in the US I found the DAW first edition from 1974 in a used book store. I think I laughed out loud with glee as this copy is in near pristine shape, and I own both these two editions and have read them both multiple times.

I already was a huge fan of Jack Vance by the time I read Shea’s novel, and the fact that I started looking for any Shea book after reading this one meant that he had that certain unique quality about fantasy writers that I enjoy—imagination and language, or style and panache. I bought every paperback I could find, and also the Arkham House collection, Polyphemus, which I have read multiple times. The titles roll off my tongue: In Yana, the Touch of Undying ; The Color Out of Time ; Nifft the Lean—all DAW books and each one its own treasure in my small library. Then many years with nothing aside from occasional novellas or slim collections published by small press publishers, until Baen Books published two Nifft sequels: The Mines of Behemoth and The A’rak. Whenever I could find his original short stories I bought the magazines, and at some point I lacked only two stories, to my great despair. Along came Centipede Press in 2008 and published a near complete and massive edition of Shea stories, The Autopsy and Others. Alas, the two stories I had been unable to locate were not included in this massive, 500+ page oversized edition.

I reviewed a couple of Shea books for Lawrence Person’s Nova Express, planned on writing more until that magazine silently vanished amid the Great Shift to the Internet in the early 2000s. Tor Books published The Extra, expanded from a short stories that originally appeared in the Arkham House collection. This was the first of a trilogy, but only the sequel appeared prior to Shea’s death, Assault on Sunrise. A third novel may or may exist. I don’t know. Other novels were hinted at in various publications.

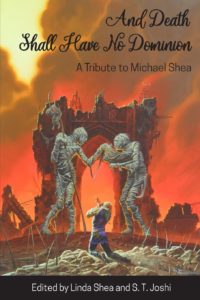

In 2016 Hippocampus Press published a tribute to Shea, And Death Shall Have No Dominion. The cover reprints Michael Whelan’s brilliant painting for the DAW edition of Nifft the Lean. Four short stories are included, only one of them a reprint. A trove of poems fill the middle section, along with tributes from the people lucky enough to have met and known Shea. Although I admired his work and wrote about it in various places, I never met him, never had his sign any of my books. Once, I received an appreciative email from Shea via Person, publisher of Nova Express, regarding one of my reviews, but I never communicated with Shea. I figured maybe one day I’d go to a World Fantasy convention, where I’d meet Shea, and learn than reality isn’t the same as fiction. It’s weird to read all the tributes to the man, the writer, and realize that he’d probably have been better in person.

Why does Michael Shea’s fiction matter? I glanced through the opening pages of Nifft the Lean recently. This is a dangerous act, as one inevitably gets sucked right into the story. Consisting of four loosely connected novellas, episodes in Nifft’s life, these tales are narrated or written down by a third party. In the first story Nifft relates a tale to a companion as they are camped for the night amid the branches of a vast tree. In that sense, it’s a story within a story within a story. The prose is vivid yet spare, with humor infused in the strangest places, such as when Nifft fights a lizard guide to the Taker of Souls and attempt a “kick in the fork,” as Terry Pratchett’s characters in Discworld would say. Nifft’s advice to his companion regarding this technique? Don’t even think about it.

Shea’s fiction often has dwelled in that intersection of fantasy and horror. Although he started out in 1974 with a semi-authorized sequel to a Jack Vance novel, Shea’s fiction already was a shade darker. His Nifft stories owes as much to Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and Gray Mouser stories as it does Vance, as Nifft rarely works alone, although his companions are not always the same. Yet both Leiber and Vance wrote mainly lighthearted tales, though some humor came across as mordant. Not so in Shea’s fiction, where the heroes venture into various pockets and sections of hell. Even his modern stories, such as “The Angel of Death” or “The Extra” (expanded into a novel), or “I, Said the Fly” contain more than a touch of dark weirdness.

I’m not much of a Lovecraft fan. Many years ago I wrote a Cthulhu mythos short story, although it was more a consequence of work and reading “Fat Face” than anything by Lovecraft. Shea had that affect, I think, as his Cthulhu stories blend the atmosphere of horror with modernity. I have yet to ride a bus without thinking about “The Horror on the #33,” but every such tale is equally memorable.

What I do find memorable in almost every story by Michael Shea is the densely rich prose. He shares this ability with Vance and Clark Ashton Smith. While some arcane or invented words fall flat in fiction, these three writers make it look easy. Sadly, most of modern fantasy consists of books with swords or wands on their covers, and deal with wizards or Robin Hood-lookalikes battling evil kings or mages. The magical prose is lacking, the sense of wonder from the writing lacking. These books are churned out by the bucketful, while stories by writers like Shea, Vance, Smith, Leiber exist these mostly in the realm of the small press. In that sense, the golden age is long gone. The good news is that in the bibliography section in this book there are several stories listed that I haven’t yet read. Maybe one day a publisher will collect the rest of those stories in a companion to The Autopsy and Others, and include those two older pieces that were left out. In the meantime, we have books like this to remind us what we had, and what is gone.